Marina Wood

Though I have had Guatemalan friends in the past, it wasn’t until I befriended my coworker Farah that I became interested in going there. She spoke of her country with such fondness and at the same time criticized our activism and our social movements here in the U.S. as compared to in Guatemala. According to her, it was life and death, and people were fighting for human rights every day. Here in the U.S. she said that people might go to a protest every once in a while, but it wasn’t direct. I was intrigued. I couldn’t imagine what she was saying and just kept impressing upon her that she just needed to get more involved, that the immigrant’s rights movements were strong. At this time we were in the midst of the walk-outs and attended the Great American Boycott together on May 1, 2006 and a counter protest of the Minute Men in Hollywood. She was unimpressed. Then I took her to see one of my favorite political scientists at a KPFK event in LA and we got to meet Michael Parenti!! I was incredibly excited. When I found her outside afterward she said she met a woman from Guatemala who is working to end femicide there.

“What? What’s going on in Guatemala?”

“Well they’re killing people, but not just women. But she wanted me to work with her, she’s in Orange County and she’s the only one doing this kind of thing here.”

I was overjoyed. Finally Farah had found something she could be involved in! But then she lost her information and was all depressed over it. That November Farah and I visited her country for the Day of the Dead and as we left the airport with her uncle and cousin, my first impression was complicated. Farah was describing “el reloj de flores,” a grass & flower clock on an island in the street we were taking to leave the city. She said it is the only thing like it in Central America. But simultaneously I was noticing that all the cars were old, and that thick black smoke was emitting from them. I asked Farah’s uncle if there were emissions regulations and he said that there aren’t anymore because there were too many cars that didn’t meet them so it wasn’t an economically sound idea. My brain grew a little as I listened to his answer and contemplated how environmental regulations affect the poor so differently.

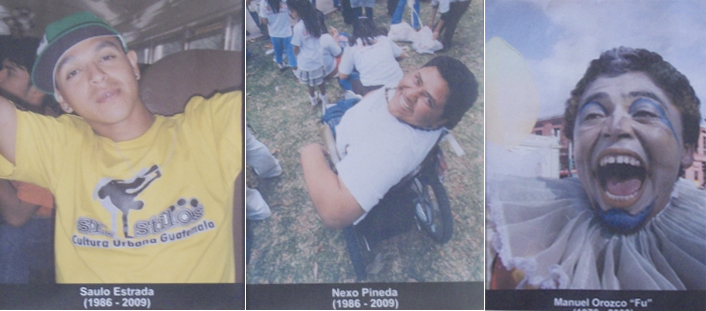

We went to Farah’s friend’s house and dropped off our luggage so we could backpack in Sampango for El Dia de los Muertos since it is up a very steep hill. Once there, I saw the most beautiful cemetery. As a lover and frequenter of cemeteries, I was pleased to see that this cemetery was incredibly colorful. The locals were placing food, alcohol and flowers on the graves; they were large crosses with the deceased’s name and year of birth/death and a person-size pile of dirt sticking out of the ground. All over, people were flying roundish paper kites and there were also huge ones that were stationary and you could walk up and see the pictures on them. It was beautiful. The women were wearing vibrant huipiles tucked into long skirts and the men were colorful too, but in pants. The women had ribbon-cloth braided into their hair and pinned atop their heads. When we left, Farah used the “sanitario” on the street. It cost money and had a sign that said “pee only” because there wasn’t water. Now, a lot more happened, but suffice it to say that we saw the beautiful lake Atitlan, went shopping, partied in Antigua, pre-screened a documentary on reformed gang members-turned activist clowns/street performers and spent a day in the jungle before returning home.

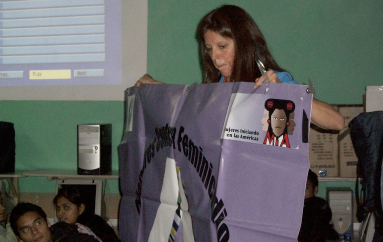

A few months later I come across an article about the Guatemalan femicide co-written by a Guatemalan woman named Lucia Munoz and Michael Parenti! I knew it had to be her and contacted her to meet us. Since I was taking a Women and Violence class at Long Beach State I decided I might as well hook up and interview her as well for a project I was working on and we went to her house. Once there, Lucia showed us a BBC documentary called Killers Paradise and I was horrified at the amount of impunity in Guatemala and the high rate of incredibly torturous rape-murder-dismemberment cases. Lucia then described how her non-profit, Mujeres Iniciando en las Americas (MIA) helps by funding and supporting non-profits in Guatemala, described her delegations, the first of which she just returned from, and her baby project, what she called the “men’s movement” that she would soon be implementing in a private school there. I was hooked. After the meeting I asked Farah if she was so excited and she said she didn’t have much time, but that it was a good cause and she would help translate. But I knew that I needed to work with Lucia more and from then on found ways to incorporate her cause into my school papers and eventually brought her to school a few times, and went on the summer delegation that next July.

The delegation was like nothing I had ever experienced before. Afterward, I came home traumatized but also longed for what we had there. Farah was right about the movement being different-I was amazed at its vitality and size. Lucia was connected to the most cutting-edge and also the most historically revered leaders and groups that were working for social change and I felt so privileged to meet them and hear what they had to say. We met with between 3 and 5 groups or individuals every day. Some people provided historical accounts of pre-war, wartime, and post-war conditions, some people invited us into their homes and spoke to us about the daughters they lost, many showed us what they are working on which ranged from documentaries about the social movements there and the hidden genocide of indigenous people during the 36 year civil war to news articles for a feminist newspaper to skill-sharing workshops for sex workers. Almost every group we met with used activism as tactics to make change: some used hunger strikes, kiss-ins (the lesbian group), graffiti art, and marches. We also went to the US Embassy and met with a Congresswoman and some leaders of the leftist party that grew out of the movement during the war and had a chance to bring the messages from the people to the decision-makers. This process was a bit tedious and frustrating but incredibly important.

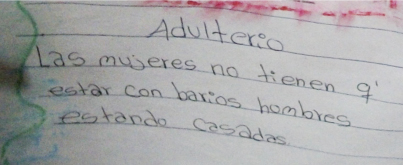

During the delegation we also had a chance to bond with some of the college students at Guatemala’s only public university and with our translator, a veteran activist named Julio who also was the facilitator for the “men’s movement” Lucia had told me about previously. He ran workshops in a couple of private schools on gender equity. The program was called “Hombres Contra Feminicidio.” Along the way we were able to see the poor living conditions of the people, and since our hotel was in a zone where you don’t want to go outside after dark, we saw what the streets felt like in the day and at night for the people of Guatemala City. There were sex workers on the corners, drunks in the alleys and excrement and urine on the streets. The plumbing there is a nightmare: you can’t flush toilet paper and in many places, you can’t flush anything. It’s no wonder that many people don’t bother looking for an indoor restroom. Also, like I noticed on my first trip, the cars and buses emit heavy black smoke which would make my eyes tear up since I wear contacts. But at the same time, when we would go to the mountains, the air would be fresher, and there was more plant life, and animals, and the indigenous people weren’t only the maids and tortilla makers but fulfilled every role because the mountains are where their communities are. And that was nice. Except that on every corner there were churches blaring protestant sermons, competing for members, and the public schools were too far to send the children to so they either didn’t go or had to pay for books, tuition, and uniforms plus transportation to a private one. It seemed like everywhere you looked, life was bitter-sweet.

When I came home, my brain was filled with experiences and memories and stories, and my life suddenly seemed so small and my activism so trivial in comparison. I brooded for awhile and wrote to my new friends and debriefed with my friend from college that came with me and finally decided that I wanted to go again. Needed to. My friend agreed to go again as well, partially to understand better because so much happened so fast and neither of us were quite fluent in Spanish, and partially because we were hooked on the movement and the urgency of it all. So we did it all again and this time I was certain I would come back feeling like that was my last trip and I saw everything and learned everything and experienced everything as well I wanted and could go home fulfilled. This trip was different in many ways, we saw different people and we even got to participate in a huge march against violence against women to the Presidential Palace, but the feeling was the same: we were there as learners not as teachers and we were plugged into the movement, same as before. When I came home again however, I again felt pulled back to Guatemala. I longed to be there, to see more, hear more, write more. In the simplest terms, I missed it.

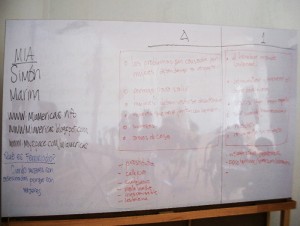

The next summer I was invited to Ecuador for a medical mission as a translator for a gynecologist and I leapt at the chance. It was also a 10 day trip but so very different it is hard to describe. We spent every day at the hospital, helping people, but never did we get a chance to meet with them as equals. There was an enormous power dynamic: we were rich American doctors coming to reach down and help the Ecuadorian people. In Guatemala, we were Americans, but we were coming to learn. We were humble and modest and ate and drank with the people. In Ecuador, we never entered the house of an Ecuadorian-we ate every meal at the hotel or at a restaurant. We weren’t there as activists, we were there as volunteers, and trust me there is an enormous difference. Also, there were huge differences in the general feeling there. It felt incredibly safer and you could even flush your toilet paper. I loved Ecuador and I felt good when I was in the hospital room, but being there only made it clear to me that I needed to go back to Guatemala, where there was more poverty and likewise more activism. When I returned, I met with Lucia and we made a plan: I would be an intern for MIA and re-instate “Hombres Contra Feminicidio” and co-facilitate with an amazing poet-activist named Simon Pedroza. This time I am going for 10 weeks and I finally get to be involved and work directly with the people. And I couldn’t be happier.

After meeting with IUMUSAC we ran all around and ended up at Centro de Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos or

After meeting with IUMUSAC we ran all around and ended up at Centro de Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos or

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network