Here at MIA, we’ve been investigating and providing information to help legislators who want to modify and reform Guatemala’s National Education Legislation to educate about and prevent school bullying and sexual abuse in schools throughout Guatemala.

Back in 2011 and 2013, the Government of Guatemala, along with the Ministry of Education and several international donors, published a Guía para la Identificación y Prevención del Acoso Escolar (Bullying) / Guide to Identifying and Preventing School Bullying, as well as a Protocolo de Identificación, Atención y Referencia de Casos de Violencia dentro del Sistema Educativo Nacional / Protocol for the Identification, Attention to, and Reference for Cases of Violence within the National Education System. You can get these documents here: http://www.mineduc.gob.gt/portal/contenido/anuncios/informes_gestion_mineduc/documents/guia_acoso_escolar_final.pdf and here, respectively: http://www.mineduc.gob.gt/portal/contenido/anuncios/informes_gestion_mineduc/documents/Protocolo_Educacion_2013.pdf

These documents are quite thorough and provide in-depth information on the topics. In fact, the Protocol breaks down different types of violence into separate categories, defining each one, explaining how to recognize them, and providing internal and external routes of reference for how to properly handle them. The types of violence identified are: mistreatment of minors and physical and psychological violence; sexual violence; violence on the basis of racism and discrimination; and bullying and sexual harassment.

It is remarkable and innovative that this information has been formally established – especially in Guatemala, where, although these types of violence are rampant, talking and learning about them are still taboo. In theory, these guides exist and should be incorporated in every public school. In practice, however, they are not properly implemented and used as dynamic tools by teachers, administrators, and school staff.

This is where MIA comes in. We are currently collaborating with Sandra Morán, a Congresswoman with Partido Convergencia. Together, we want to raise awareness and provide information that may be used to advance legislation that ensures that the Guide and Protocol are properly enforced in each school and classroom. It simply doesn’t do much good to have all the information officially printed and made available to the public, if the utilization of these tools is not enforced.

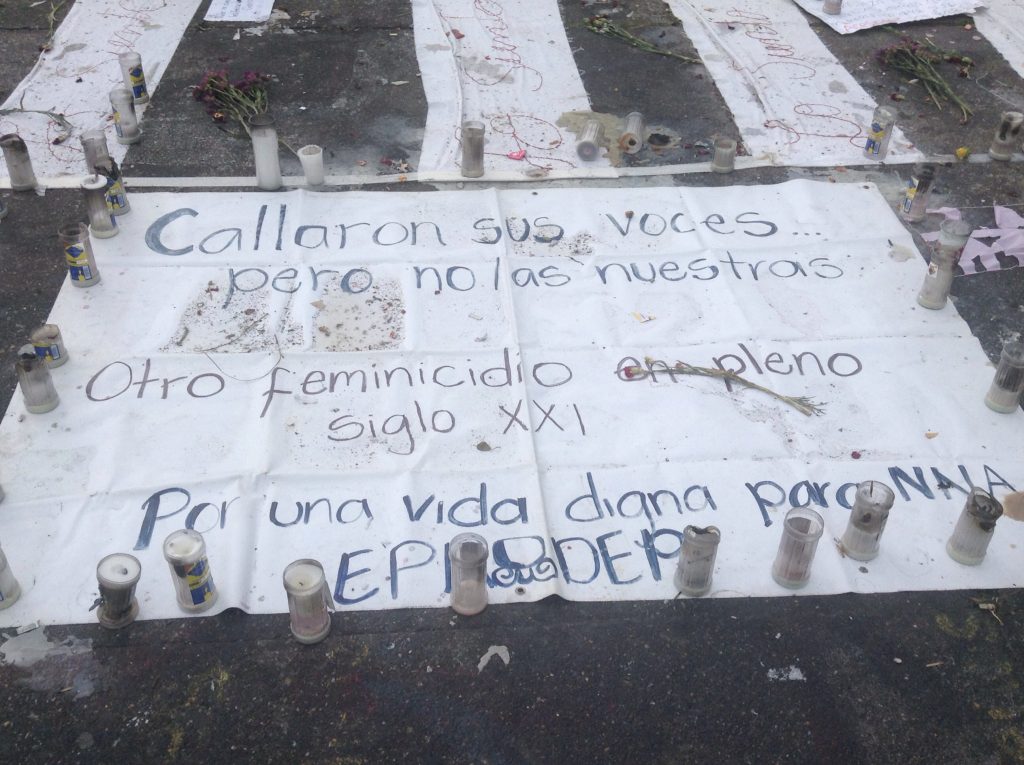

Sandra Morán is a really interesting and ground-breaking politician. She was elected in September 2015, amidst the corruption scandal that involved many in public office, and took office in early 2016. She is a staunch feminist in a machista country where being a feminist is radical and even dangerous. She is also openly gay, in a place where violence—and even murder—is perpetrated against homosexual and trans people. Sandra has said, “In Guatemala, to be a feminist is not welcomed, to be a lesbian, even less so. But the fact that I have always been transparent about who I am – a lesbian feminist – took away that weapon from those who use misogynist, sexist, and homophobic attacks as a political strategy.”

Sandra has long been an activist. She was born in 1960 (the year Guatemala’s internal armed conflict began) and from a young age, expressed her anti-military, anti-violence and repression sentiment, joining the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres, EGP), when she was a teenager. She then went into exile in the early 1980s, when the dictatorship and governmental brutality were most severe, and spent time in other Central American countries and Mexico, until the conflict was officially over with the signing of the Peace Accords. Upon her return, she became part of the Women’s Sector of the Assembly of Women for the Peace Accords, and later the coordinator of the Women’s Forum. Over the past 20 years, she has promoted and participated in different feminist and lesbian collectives, such as the women in exile collective Nuestra Voz (Our Voice); the lesbian collective Mujeres Somos (We Are Women); and the Colectivo de Mujeres Feministas de Izquierda (Feminist Leftist Women’s Collective).

Sandra has a strong agenda to make more visible LGBTQI rights and gender diversity and equality. As she has expressed, upon her election and with regarding her everyday fight: “Lesbian identity in Guatemala is taboo. It was necessary to show it, not only to break that taboo, but more so, it gave the opportunity for the LGBT community to have a representative. I knew that identity was going to be used against me. So I took from them the power they could have had to use it against me.”

She is pushing strongly to include school bullying against LGBTQI students in the Guide to Identifying and Preventing School Bullying, where the unique and persistent ways in which these students are harassed and bullied are specifically detailed. Using homosexual slurs such as hueco, maricón, marica, culero, among others, is extremely widespread against students of all ages, and it is time that this violence is addressed head-on.

At MIA, we are very excited to be working to provide information to Sandra Morán and her party to really make in-roads and lasting change within the Guatemalan education system on identifying and properly addressing violence and bullying in schools. Her energy and deep desire to create change are contagious, and she seems prepared and driven to confront and and all obstacles that would prevent advances towards gender equality and identity. Stay tuned to read more about our collaboration and achievements!

If you’d like to read more about Sandra Morán in the news, The Guardian has a great article: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/feb/11/guatemala-feminist-lesbian-sandra-moran. The Nobel Women’s Initiative conducted an interview with her: https://nobelwomensinitiative.org/meet-sandra-moran-guatemala/. And Guatemala-based Plaza Pública has an in-depth article in Spanish: https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/sandra-moran-una-feminista-en-el-congreso.

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network