Shirley Aldana is a PhD student at Adler University and is working with MIA for her internship. She will be documenting her work in future blogs, but for this first blog, she gives a perspective on how she got here and why she is working with MIA.

— Chris Hill, Secretary

———————————————————

“It was the nation’s architects who laid a foundation rooted in slavery, capitalism, and an ideology that for generations has stigmatized slaves and their descendants as inferiors. The foundation has lasted far longer than the tools that were used to dismantle the most egregious practices of racial subordination.”

Fredrick C. Harris, ‘James Baldwin, 1963, and the House that Race Built’

My Immigrant Story

How does someone decide one day that they will leave everything they know and love? Knowing that their very existence and survival will depend on happenstance and the hope on a shared humanity and good will. The push and pull factor of immigration is not new to the human race, if you believe in evolution like me, then you are familiar with the “Out of Africa” theory which explains why my DNA is agglomeration of Iberian, East and West African, Southeast Asian, Asian, and European ancestry, but I digress, and perhaps will return to that topic at a later time. For many people in Guatemala and other countries in Latin America and around the world, the immigration push/pull factor is most likely is one of fear, despair and search for economic opportunities for their families.

Like MIA, Mujeres Iniciando en las Americas’ founder, Lucia Muñoz, my family was also impacted by the mass exodus of mothers and fathers leaving their children behind in the care of family members, and oftentimes strangers, in the pursuit of work in order to provide the basic needs lacking back home. People might find it surprising that mass exodus from Guatemala to the United States specifically, has waxed and waned since American industrial corporations positioned themselves in Guatemala as the foothold of international commerce according to “Immigration – A Central American Problem” (Filsinger, 1911).

I believe it is egotistical ignorance on the part of the elitist and anti-immigration supporters in the United States, often found in academics, politics, journalism to discuss immigration issues in black and white binaries and absolutes. I am not going to not say that that the push/pull factor of Guatemalan exodus is founded on US capitalist and economic exploitation, and prosperity of this great country from colonial through today continues to be built on the backs, sweat, blood, tears and hopes of those citizens it refuses to acknowledge and recognize.

However, I want talk about the aftermath of the push/pull factor from my Guatemalan immigrant experience. I was forced to leave Guatemala with complete strangers to be reunited with my mother in the United States of whom I had vague memories, but yearned to see. Coming of age as an “illegal” immigrant in the United States, was one of fear, confusion and disconnect. Reuniting and reconnecting with my birth mother in the United States intersected difficult issues of abandonment, reunification, belonging, and identity. Identity.

There is a saying that the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” and for me, there were pieces missing in the puzzle; the yearning to understand my Guatemalan culture, and particularly to reconnect with an identity I had abandoned for the sake of assimilation brought me to a crossroads of looking deep into how I had internalized cultural messaging in my life. I recall a particular moment I was proud to be Guatemalan, it is frozen in time, burned in my heart.

The Guatemalan Peace Accord of 1996 was signed and it was all over the news, I had learned about Rigoberta Menchu and pride for Guatemalan indigenous Mayans grew in me. I was so happy I called my family in Guatemala. My grandmother had passed away a few months before, and I spoke to a dear aunt who I had (have) so much love and admiration for, I carried on about Rigoberta Menchu. What she said to me shattered my heart and set me on course I am now navigating, and one I am honored and privileged to be on. She said that Rigoberta Menchu was a dirty no-good lying “india” – as a Guatemalan immigrant I had experienced discrimination and racism, and never in my heart of hearts thought its roots ran so deep and long, and in my family.

For me, being my authentic self has been a long and mindful process. My experience as a Guatemalan immigrant coyote-trafficked-child exposed me to things no child should be exposed to, and it also formed the binaries of what I perceived as injustice and justice. My first experience with racism was as a fifth grader at Will Rogers Elementary in Santa Monica, California. Even with my broken-English I became good friends with a porcelain skin, blue-eyed, blonde hair classmate. She invited me to her house, and when her mom heard my broken English, she told my friend to get that Mexican out of her house.

The lens of social justice formed early on in my life, even before I migrated to the United States in 1978. In Guatemala, as a child I saw a female neighbor beaten to an inch of her life and no one intervened. I saw a homeless woman give birth in my grandmother’s bakery. I saw a man try to break into our home and shoot into our living room. I saw the fear and anguish and tears of my grandparents when an uncle was kidnapped and returned a week later. As child, the 1976 earthquake left us homeless, we lived in make-shift tents outside our inhabitable homes, and we stood in long-lines to get a ration of food for many weeks, months for others.

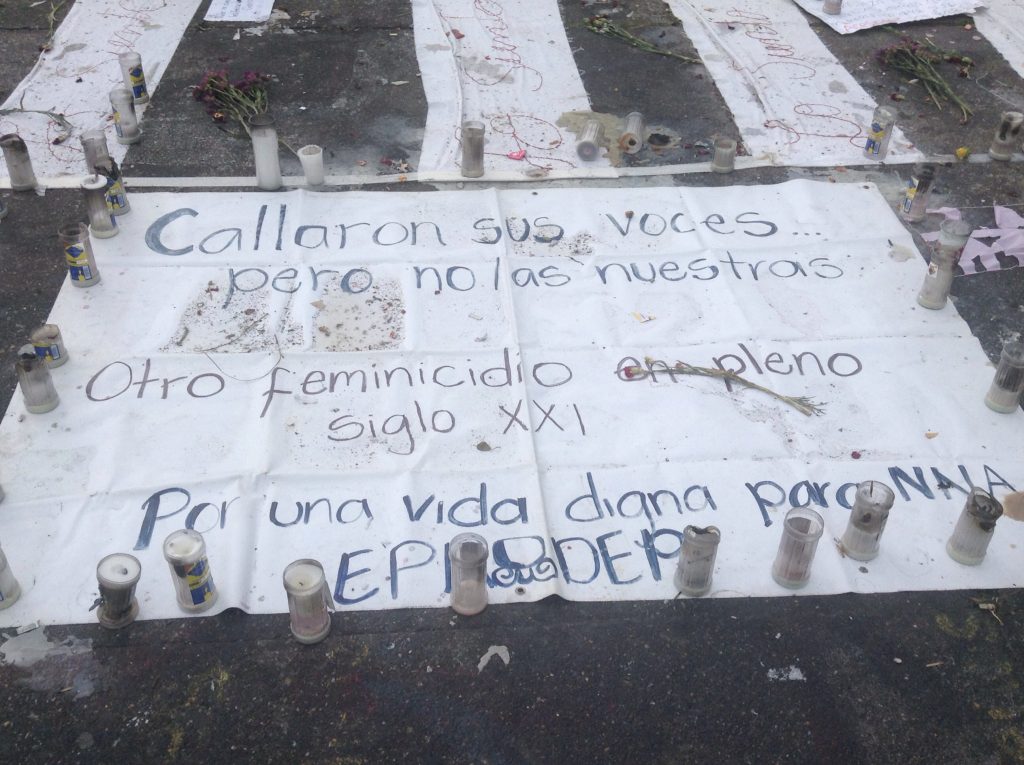

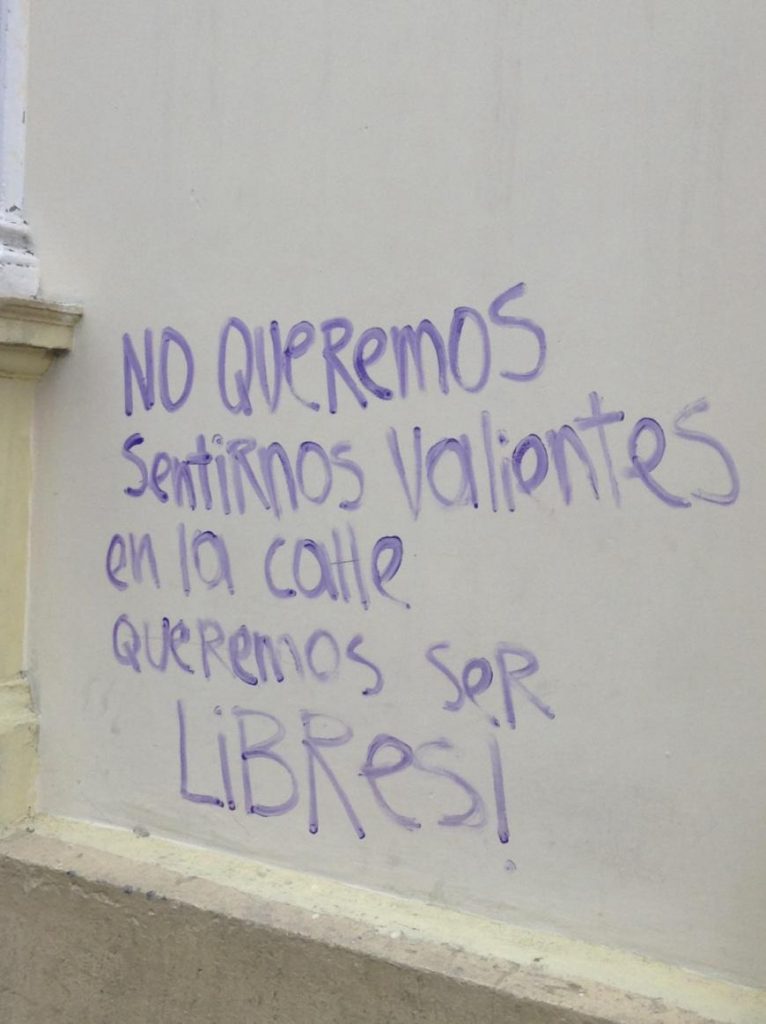

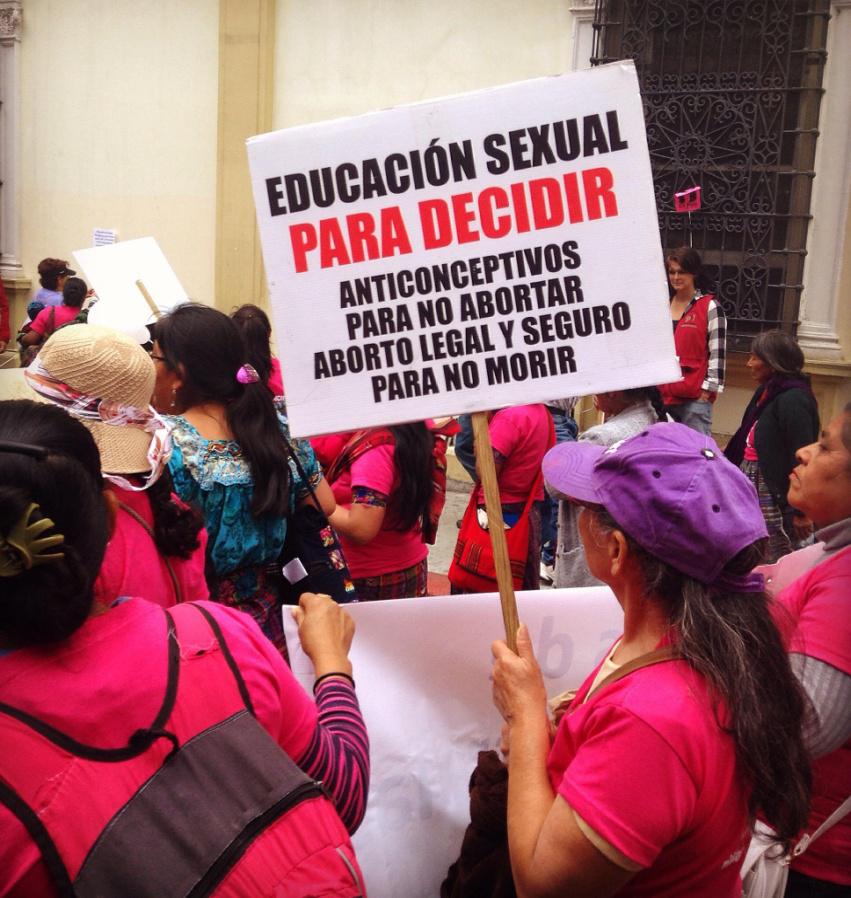

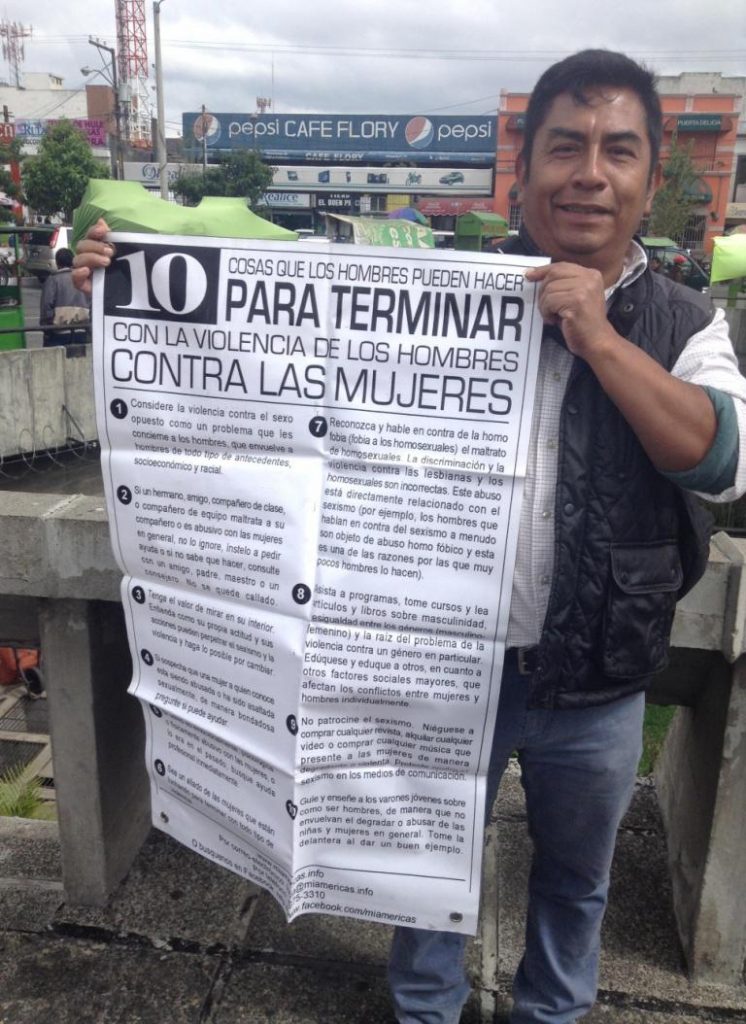

While these types of events evoke caring concern, themselves may not fully paint the image and the urgency from plight many Guatemalans actually experience : crimes against humanity, organized crime, gang violence, drug and human trafficking, domestic and gendered state violence, child abuse, child rape and forced marriages, lack of health care, lack of education, high unemployment, lack of clean water due to environmental exploitation, earthquakes and natural disasters.

Furthermore, Guatemala continues to endure a complicated and painful history, we are descendants of Spanish conquistadores, and Mayan warriors, and our cultural beliefs are an agglomeration of all that is beautiful from both worlds. But our political structures and policies have been constructed by the worst of American Capitalist Imperialist White Supremacist values.

When I think about my life experiences as an immigrant child trying to assimilate, and negotiating ways of belonging, it is thought provoking as well as opening old wounds. When I think of the ways that society operated/operates still in my life and how it prescribes meaning to peoples lives, it seems almost unthinkable of the capacity of the vast human experiences and ability to function and find resolve to move forward, but most importantly function in a system that can be oppressive and restrictive if you weren’t born with the preferred phenotypes, or geographical boundaries, or the class structure, or gender expression, or set of cultural beliefs and values.

When I consider the act of being wholly authentic, I reflect on a double consciousness, feeling of otherness as I saw myself through the eyes of others, as an non-white immigrant. I took into consideration forms of being transparent as one of an interconnectedness of beliefs, values and actions, but what happens when our beliefs, values and actions hurt and marginalize others?

To paraphrase James Baldwin “we operate under the beat of the language that has produced, oppressed & dehumanize us.” The formation of language is a powerful tool of oppression, as well as healing and belonging. Adrian Favel defined the politics of belonging as “the dirty work of boundary maintenance (1999).” He said that we have emotional attachments to our social environments, and we place boundaries and put value judgments on others and ourselves. That we “operate” in “imagined communities” under “hegemonic political powers within and outside that community” where participation of citizenship are “interrelated to status, entitlements and membership.” What happens when we have been excluded from participating in defining our identity? Drawing from writings of Teresa Cordoba in “Anti-Colonial Chicana Feminism:

“It is the pain of the present, however, that keeps the historical memory fresh… It is by strategic essentializing that we are able to create an important practice against the hegemonic ideologies that define us in ways to silence us and control us.

It does not provide a final destination, but a journey by which we may find our “multiple identities” so necessary in the fight against colonization (racial oppression). It is the fight for social change, for our own self-definitions and our own decolonizing spaces.

In “Power and Knowledge: Colonialism in the Academy,” begins with the premise that breaking silence against oppression is an important anti-colonial act because silence and compliance are so critical to maintaining exploitative relationships.”

I wholeheartedly believe that while Guatemala will celebrate its 200 years of independence this year, Guatemalans continue to be subjects of American imperialism and have internalized racist and political structures perpetuated against ourselves. To answer question “how does someone decide one day that they will leave everything they know and love?” it seems to me the answer is liberation. It is northbound. But not without a new set of obstacles. For those us who long for a true democratic Guatemala, with prosperity and liberation, I hope you are inspired by the words of Sara Curruchich (2017) a Guatemalan music artist:

“One of the biggest fears of my family, specifically of that of my mother, that I would go through the same [suffering] that she had gone through”

“I believe that as women we are all discriminated against”

“As an indigenous woman, we are double discriminated ”

“I knew that somehow those types of thoughts [racism and hatred] have to change … and although they hurt [my experiences] … those who have to change are those people”

“I talk [sing] about my grandmother’s [indigenous] textiles … [because] of the wisdom, each one of us, as women, is sharing … a [indigenous] textile is a canvas, a canvas is made collectively”

“We are all actors and actors of change … we cannot be indifferent to everything that happens”

References:

Córdova, T. (1998). “Anti-Colonial Chicana Feminism.” New Political Science 20.4 ;379-97.

Crowley, J. (1999). ‘The politics of belonging: some theoretical considerations’, in Andrew Geddes and Adrian Favell (eds), The Politics of Belonging: Migrants and Minorities in Contemporary Europe (Aldershot: Ashgate 1999), 15/41.

Filsinger, E. B. (1911). Immigration—A Central American Problem. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 37(3), 165-172.

iniciativaT. (2017, May 24). Sara Curruchich. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHJJoP5YF28&feature=youtu.be

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network