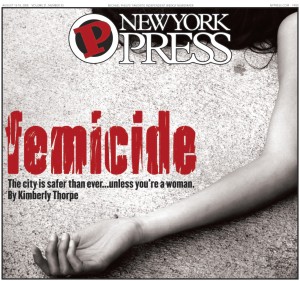

By Kimberly Thorpe

When the cops arrived, Patricia Whitley was already dead. They found her tucked into bed as if asleep. They found her son also dead in the bathroom. The blood on the walls, tub, floor and sink had been sopped up.

When the cops arrived, Patricia Whitley was already dead. They found her tucked into bed as if asleep. They found her son also dead in the bathroom. The blood on the walls, tub, floor and sink had been sopped up.

The officers knocked on the door and heard the pitter-patter of quick, light feet running to it. A sobbing, 15-year-old Zina Whitley threw the door open and fell into their arms. Cops noticed a figure move on the couch in the corner of the living room. A man stood up, calmly stepped toward them, and denied doing anything. Cops wrapped him in a sheet and took him away.

The two police reports written that day are notable for their brevity. “Upon further investigation, [officer] discovered [victim] DOA lying face up in bed,” read one. The other report stated only, “Discovered [victim] DOA placed in a plastic bag.” Both corpses were pronounced at 14:49 hours, only minutes after police arrived. Police protocol kept them from writing strangled or stuffed to describe the 46-year-old woman they found in bed or the 8-year-old boy they found in bags with his head cut off.

That day was three years ago, on Thursday, Aug.18, 2005. It was a day when Whitley’s co-workers at the city’s Department of Health expected her at the office. Zina probably planned to take her brother Malik downstairs to the playground outside their subsidized co-op in Coney Island.

It was a year after Whitley filed the first of two domestic incident reports with the 60th Precinct. It was also the day that Patricia Whitley became one of the 35 to 40 women who die each year at the hands of an intimate partner in New York City.

In a city that is touted as one of the safest in the country, domestic-partner homicides persist. Last year, NYC’s homicides numbered 496, which is a commendable number, especially compared to the early 1990s when the number was well over 2,200. Since the late ’90s, however, the number of women killed by their partners hasn’t declined; it’s difficult to make headway in preventing this type of killing.

Police don’t report homicides by gender, so this fuzzy segment of murders is rarely highlighted. Police categorize all family related homicides together, which some argue, conceals the true risk to women. Domestic violence advocates, public health researchers and city officials have been locked in an unproductive shuffle, stumped by how to define and then attack this persistent type of crime many experts call “femicide.” And now that the city and the country face recession, advocates worry social services stand to lose funding.

Around 100 women are murdered every year in New York; nearly 40 of those women will be killed as a result of domestic-partner homicide. At least 11 women in NYC have already been killed at the hands of a partner since April.

While the Whitley family is black, this issue is in no way limited by race or economics. On May 31, Margaux Powers, a 26-year-old, white Ivy Leaguer was found with her throat slit in her Chelsea apartment bathtub. A note from her boyfriend apologizing for wrongdoing was found in another room. Jessica Tush, a 19-year-old teenager from Staten Island, was found in a shallow grave in New Jersey in April, after missing for two days. Her estranged boyfriend was arrested and charged.

Victoria Frye is a young epidemiologist at the New York Academy of Medicine, who has been studying femicide for 10 years. “If the general homicide rates continue to go down and the intimate-partner femicides stay the same,” Frye says, in exasperation, “pretty soon we’re just going to have every murder be a woman killed by her partner.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

On the day before she was murdered, Patricia Whitley came home from work and took her kids to their Aunt Carla’s house in Flatbush. They caught up, but soon the conversation turned to a topic Pat, as her friends and family called her, was sick of hearing: Carla told her once again that she had to get rid of that man, Christopher Patterson.

Patterson, a bulky 32-year-old black male with a thick neck and wide eyes, met Pat out in Manhattan on the street one day. The first time the kids ever heard of him was when Pat told them her boyfriend was moving in. Pat’s sister, Carla, believes that Patterson took advantage of her younger sister’s lack of street smarts—that he was a predator.

“Pat was like a pigeon, and he just watched her,” Carla says, holding up and extending an imaginary telescope to her right eye. “He scoped her out.”

The family lived on the 13th floor of one of the 24-story Warbasse Housing buildings in Coney Island. From the apartment window, you could see the Coney Island Wonder Wheel.

Pat’s kids, Zina and Malik, didn’t like the idea of a stranger living with them. But Pat thought he would be a good father figure; their actual father was never around, and if he did show up, he was usually drunk.

Patterson’s habits bugged Zina. He used to watch pornos while her mom was away at work, smoke pot and put “snotballs” on the walls, says Zina, who turned 18 this February. Pat worked at the health department for 15 years, processing health code violations. When Pat got home from work, Zina would point out all the gross and annoying things Patterson had done. Her mom would just laugh them off.

Patterson seemed like he was always between jobs, getting hired, then fired. At some point, he and Pat started arguing. People at her office began to suspect something was wrong and neighbors were concered, but no one knew how to intervene. Then Pat started to get scared. She called the police on New Year’s Eve when Patterson showed up unexpectedly and started a fight. He was gone by the time cops arrived. Pat had filed the first domestic incident report on Aug. 7, 2004, after Patterson called her repeatedly and threatened to hurt her.

The biggest risk factor of femicide is a history of violent behavior by the man in the relationship, according to experts. The problem then lies in who is paying attention.

Some women call the police. Most don’t. According to NYPD Domestic Violence Unit chief Kathy Ryan, 77 percent of last year’s domestic violence homicide victims, a category that includes men and children, had no prior police report against their abuser.

So, it stands to reason, a lot of victims are going elsewhere for help. Many public heath researchers and epidemiologists thought to focus on primary care physician offices and hospitals, where battered women often show up with injuries.

Jacquelyn Campbell, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, has spent decades studying femicide. She developed a “Danger and Risk Assessment Tool” that health professionals use to rate the risk of a woman’s abusive situation. Risk factors include: “Have you left him after living together during the past year?”; “Is he unemployed?”; “Do you have a child that is not his?”; “Do you believe he is capable of killing you?”; “Does he follow or spy on you, leave threatening notes or messages on answering machine, destroy your property, or call you when you don’t want him to?” Then the total yeses are tallied. Campbell warns that most women do not accurately perceive their risk and that over 70 percent of completed and attempted femicides happen when the woman is trying to leave.

. . . . . .

The night before the murder, Pat, Zina and Malik returned from Carla’s house, and saw Patterson sitting on a bench outside waiting for them. Upstairs, Zina listened as her mother yelled at Patterson, promising to kick him out the next day. After the fight, Zina saw Patterson on the floor in the hallway, rocking back and forth, mumbling something.

Zina asked him if he was OK, but he wouldn’t answer. She walked down the hall to her mother’s bedroom.

“Kick him out now,” she said to her mom. “Don’t wait for tomorrow,” she pleaded repeatedly. But her mother answered the same way she had been answering her own sister and all the neighbors and co-workers who had been telling her the same thing. “No,” Pat said. “It’ll be OK. I’ll do it tomorrow.”

Zina had a bad feeling. She asked her brother if there was anything she could get him. He asked for pizza. She made him some and then tucked him into bed. Her mother kissed her goodnight in the hallway. “That was the last time I saw them alive,” says Zina, who lives in the same building, just 11 floors below.

Three years after this murder and others like it, there still hasn’t been a meaningful effort to cut out intimate-partner killings. “I do think there was more concerted action four or five years ago, people found out it could happen to anybody,” says Jacquelyn Campbell, the author of the risk assessment tool. “The public’s attention to issues is fickle. I think there are a core of people as passionate as they ever were. I’m afraid now with the economy tied again and the state budgets tied again, we’ll see cutbacks in services.”

The city turned its attention to curbing homicide in the early 1990s. Back then, NYC was known as the murder capital of the world. New York was in the middle of the crack-cocaine epidemic and strangers were murdering strangers over drugs and money. Money was available for anyone willing to look at how to lower the city’s murder rate.

The New York Police Department added a Domestic Violence Unit in an attempt to intercept those kinds of private crimes that happen behind closed apartment doors. NYPD Domestic Violence Unit director, Kathy Ryan, says that today there are over 300 domestic violence prevention officers and detective investigators throughout all the precincts.

Some federal money found its way to another New York City office, the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. There, a nutritionist named Susan Wilt volunteered to use the funds to build a database that would track more closely the demographics and causes and relationships of those murdered. Quickly she began focusing the database on women. Soon, she and her team of epidemiologists and graduate student interns began to notice that the only area of homicide not declining like the rest was intimate-partner femicides.

This femicide database, as it became known, quantified what many in the advocacy field already knew. But the numbers are different from those released by the NYPD. These researchers used medical records and reports from the medical examiner’s office to paint a nuanced picture of the situations that culminated in a woman’s murder. The most recent report from the department of health tracks femicides up to 2004. The report, Femicide in New York City, Surveillance and Findings, 1995-2004, showed that the overall number of women killed dropped alongside with the overall homicide rate in the mid-’90s. However, between 1998 and 2004, the number of women killed annually has remained around 100. Between 2002 and 2004, 37 women on average were intimate- partner femicides.

The city is under a lot of pressure again, as it was in the mid-’90s: this time not to curb a reputation as murder capital, but to keep it as one of the safest big cities. But, from July last year, there has been almost a 9 percent increase in homicides in the city, according to the NYPD. Although the police don’t report crimes by gender, overall rapes from this point last year have increased over 10 percent, suggesting that violence revolving around sex is on the rise.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Zina woke up to her nightmare. Her brother was dead in the bathroom and Christopher Patterson, her mother’s boyfriend, was seething. He pushed Zina into the master bedroom and tried to rape her on the bed. She was lying next to her mother’s dead body.

“She was dead but her body was shaking,” Zina says. “I kept screaming her name and her body just started shaking. Her soul was trying to release from her body.”

According to Zina, Patterson didn’t rape her because she said she would do whatever he wanted. So he made her put her brother in bags and clean up the blood.

“I was holding my brother’s body,” Zina says, holding out her arms in front of her as if accepting a small baby. “It was sunny outside… that was the first time I started believing in God.” She pauses. “I started believing in God again when I picked up my brother’s dead body…” but tears stop her from finishing the thought.

When she was done in the bathroom, she hid in her room. She braced the door so Patterson couldn’t get in, and she could hear if he tried. Then she got into her closet and waited. Then she called the police.

“When the police knocked, I ran out and past him. He was lying on the couch.”

Coincidentally, both Patricia Whitley and the creators of the femicide database worked for the health department, although in different fields.

When Pat Whitley was murdered, the department’s epidemiologists were contacted immediately. Researchers organized a town hall kind of meeting inside the department for anyone grieving or curious to talk about domestic violence in their own lives, about 200 health workers, mostly women, attended.

The department worked with a domestic violence advocacy group to coordinate a citywide campaign to get more bystanders—neighbors who hear domestic violence—to speak up.

“[Our] stuff was out there for ever,” said Susan Wilt, who began the femicide database but who has since retried from the health department. “We didn’t need Patricia killed to start looking at this stuff. Our data has been there.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Not much moves before noon inside apartment 2B. A naked bulb shows in the ceiling, but it’s not often lit; the only light comes from a window facing southwest. At the end of the hall, the door to Zina Whitley’s room is still shut. It takes her close to an hour to get dressed and come sit in the living room.

In the meantime, her aunt, who she now calls “Mom,” is sitting near the only window in the living room in slippers and a rough-looking maroon bathrobe. Carla Whitley breathes heavily. She says today is not a good day for her, the HIV medication she takes is knocking her out.

“Zina!” she says, lumbering halfway down the hall to make her shout more audible. “The lady’s here!”

Zina comes out and says hello while looking down. She’s a pretty girl, with athletic shoulders and a long, graceful face. Her hair is twisted and gathered to the right side of her head in a fashion clip. She’s wearing white tube socks.

She’s dragging her left leg and most of her left side with her. Carla asks her in a low voice if she’s OK. Zina nods, and Carla shuffles off down the hall to lie down.

Zina then chooses a tall stool to sit on. It’s an effort to get up, and then she uses her right arm to help her left into a position.

Last year, at 17, Zina had a stroke that left her in NYU hospital for six months. “The doctors thought it was stress,” Zina says, guessing the next question from her listener. “But there are more and more studies saying that strokes happen to young people, too.”

Patterson was sentenced to two consecutive 25-year terms in prison for both murders, but Zina says she’ll never feel safe unless he’s dead.

Her bedroom still looks childlike. Her walls are painted a flat blue. Her bed comforter is pulled taut over the bed, and decorative pillows are gathered near the headboard. A row of crammed stuffed animals look out over her bed and room. On the left-hand wall just as you enter are the photos of her mom. Just as a teenager would, the developed film is taped in a playful order with some shots of her mom taped up diagonally.

She says she can sometimes go a whole day without thinking about what happened. It’s been hard for her to relive the experience by telling her story and she’s crying now. She excuses herself. It’s time to go. As she sees a stranger out, she says between sobs, “Have a good day.” The door closes gently.

Eleven New York City women have been killed by intimate partners since April.

The body of Margaux Powers, a 26-year-old Cornell graduate, was found in the bathtub of her Chelsea apartment, where she lived with her boyfriend. The boyfriend, Jonathan Smith, 34, jumped to his death from a Financial District building before police could catch him. About 25 percent of the perpetrators of intimate partner femicides between 2002 and 2004 committed suicide after the homicide.

The body of Margaux Powers, a 26-year-old Cornell graduate, was found in the bathtub of her Chelsea apartment, where she lived with her boyfriend. The boyfriend, Jonathan Smith, 34, jumped to his death from a Financial District building before police could catch him. About 25 percent of the perpetrators of intimate partner femicides between 2002 and 2004 committed suicide after the homicide.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Police accused Thomas Paolino, 19, with the murder of Staten Island teen, Jessica Tush, also 19, whose body was found in a hand-dug shallow grave in New Jersey in April. Days before the murder, the couple had broken up. The majority of femicides occur during a significant change in the relationship, such as a break-up or a pregnancy.

Police accused Thomas Paolino, 19, with the murder of Staten Island teen, Jessica Tush, also 19, whose body was found in a hand-dug shallow grave in New Jersey in April. Days before the murder, the couple had broken up. The majority of femicides occur during a significant change in the relationship, such as a break-up or a pregnancy.

http://www.nypress.com/print-article-18662-print.html

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network