By A Volunteer

“In theory, the Guatemalan government has a clear line of work that consists of maintaining and regulating any aspect of social relations (labor, political, economic, social, familiar, and institutional) within its territorial confines. In practice, it is evident that it only cares about the protection of the dominant and most powerful, and this conservative and misogynistic way of thinking and acting justifies that abortion is a crime but that the aberrant deaths of dozens of scorched girls is the ‘responsibility of everyone.’”[1]

Several men lighting candles. Sign: “CORRUPTION is what killed the girls!”

My previous blog post discussed March 8th: International Women’s Day, the march in Guatemala City with photos, and my three years with MIA. Tragically, March 8th 2017 also marked a devastating fire that took place in a shelter called Hogar Seguro (which ironically translates to Safe Home) for children and adolescents. At the time of writing, 40 adolescents have died, several severe burn victims have been transferred to hospitals in the United States for skin graft surgeries, several others remain in critical conditions in Guatemala, and many survivors are being relocated to other shelters throughout Guatemala. All of the victims are female. It is shocking and heartbreaking and incomprehensible. The government officially declared a State of Mourning from March 8th-10th, countless investigations are being done to get to the bottom of this tragedy, and civil society organizations and individuals alike are gathering in Parque Central to hold memorials for the victims and demand justice and accountability from the State. It seems as though everyone in Guatemala is mourning and desperately angered by the negligence and abuse that took place in the shelter.

A very brief version of the series of events leading up to the fire is the following. On the evening of March 7th, a group of adolescent girls in shelter started an uprising, and sought the help of some adolescent boys. One of the reasons determined for the uprising is that the adolescent girls could no longer take the abuses and sexual violence perpetrated by the teachers, administrators, masons and guards who worked at Hogar Seguro. These are some accounts:

‘“You can’t leave this room until you give me oral sex,’ ordered teacher Edgar Ronaldo Diéguez Ispache to 12 and 13-year-old students, as they tried to leave the classroom in which they received 5th and 6th grade classes. Not one was able to leave nor avoid the sexual abuse.”[2]

“The same teacher ordered girl and boy students to walk around the classroom naked in front of their classmates. One of the masons, José Roberto Arias Pérez, raped a mentally disabled girl. An alleged worker, described in one of the 28 legally filed complaints to the Secretary of Social Welfare as Joseph, forced some of the girls to have sex with him as he took them out of and away from the shelter.”[3]

In the middle of the uprising, the staff, aware of what was happening, opened the doors and screamed, “If that’s what you want, then get the fuck out of here!”[4] The adolescents ran out of the shelter and hid in the surrounding forest. A little while later, once they were captured around 10 PM, the adolescent boys were beaten by the police, while the adolescent girls were manhandled. Afterward, they were separated: the boys were locked in the auditorium and the girls were locked in a part of the school. Between roughly 12 AM and 8 AM on March 8th, between 52 and 60 girls and adolescents were forced to stay locked in this area, unable to leave even to use the toilet. Dozens of police and guards were stationed outside the auditorium and the section of the school. Around 8 AM, some of the girls set fire to a mattress, which quickly spread to the other mattresses across the room. Once the fire started, the girls screamed for help and banged on the doors but the police wouldn’t open the doors.[5]

Some of the adolescent boys provided the following testimony:

“Around 8:30, we started to smell a burning stench, and I don’t even know how we opened the door of the auditorium, in order to go and help the girls because they were burning. But the police didn’t allow us to help them and they began to hit us. No one helped the girls, and we weren’t allowed to help them either.”[6]

“This body is mine… It won’t be burned! It won’t be raped! It won’t be murdered!” #ItWasTheState

There are many intersectional elements to this tragedy. First of all, the conditions of the shelter were abysmal. Reports had already been filed over three months ago by the Human Rights Ombudsman, when it requested cautionary measures with the Inter American Commission on Human Rights. Moreover, UNICEF explained on repeated occasions to authorities and the media that an institution like Hogar Seguro was an unsafe environment for children and adolescents. It was designed to hold a total of 500 children but had approximately 800 at the time of the fire.[7]

Secondly, the children and adolescents in Hogar Seguro come from very precarious situation and poor backgrounds, whose families couldn’t care for them or who do not have parents or family members to care for them. Many suffered abuses at the hands of their guardians. In fact, according to the Secretary of Social Welfare, Hogar Seguro is an institution that “provides refuge and shelter to children and adolescents from 0 to 18 years of age, who are victims of physical, psychological, and sexual violence, who have disabilities, who are abandoned, who are homeless and living on the streets, who suffered from addiction problems, who are victims of human trafficking and sexual, commercial, labor, economic exploitation, or who are victims of illegal adoptions.”[8] Basically, children and adolescents were rescued from these horrible conditions and sent to Hogar Seguro to be protected and receive the care and attention they needed, under governmental mandate.

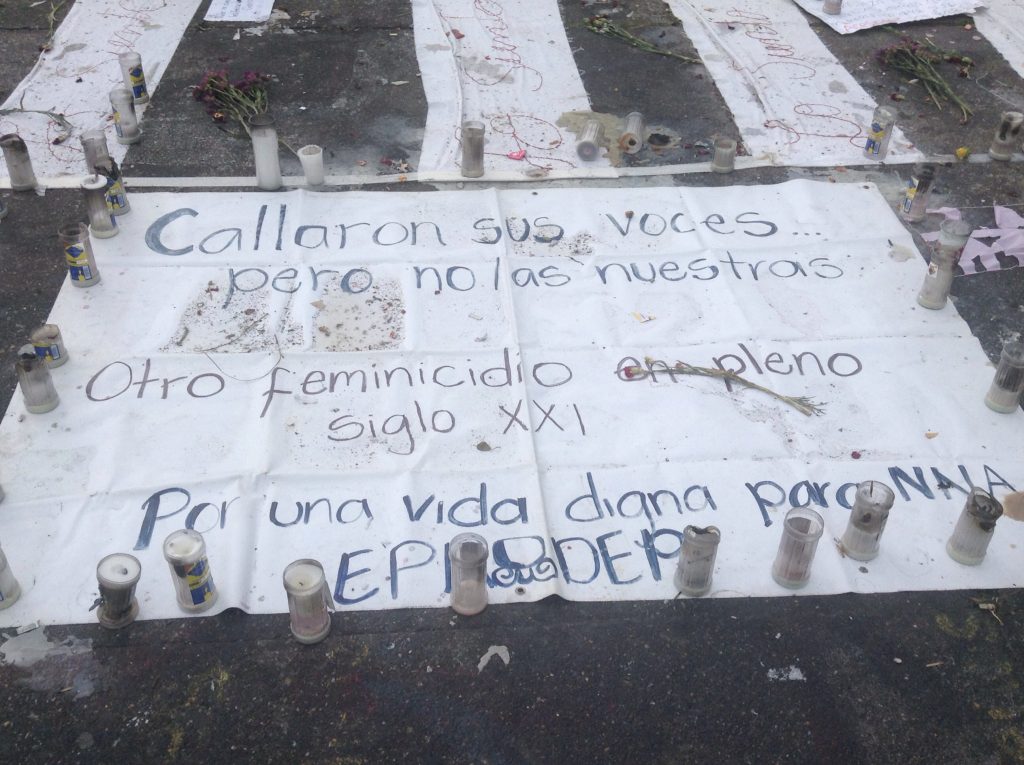

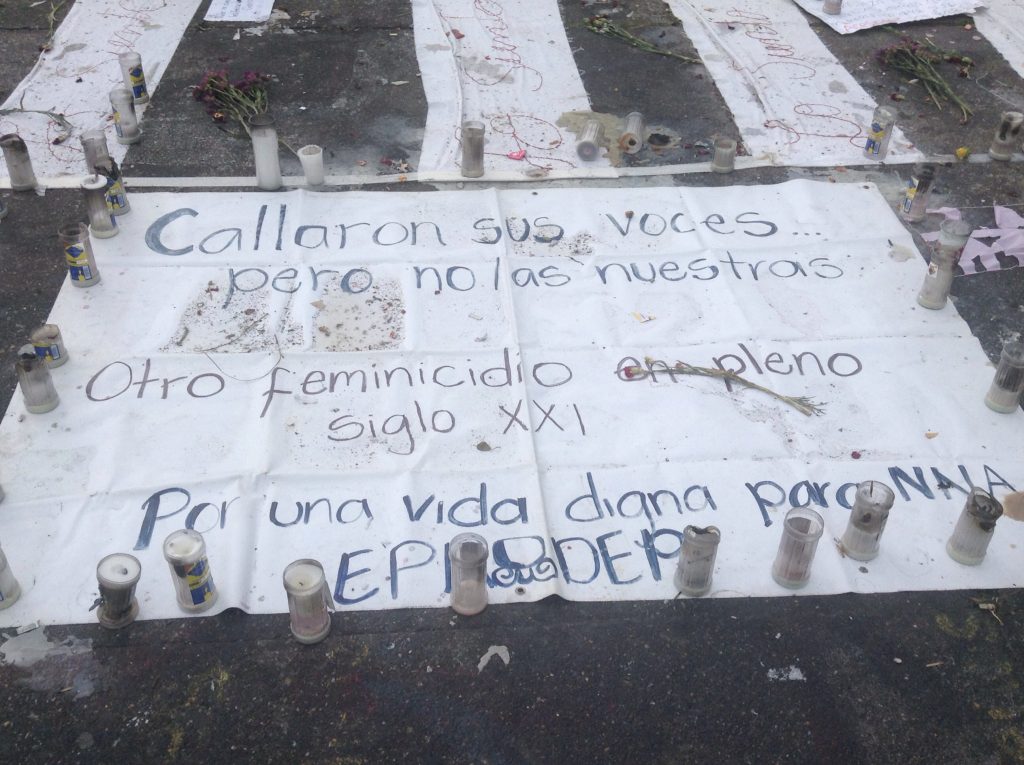

“Their voices have been silenced, but ours aren’t. Another act of femicide in the 21st century.”

Thirdly, the issue of gender: I already stated it above, but all of the victims of the fire were adolescent girls. Some had been raped by fathers, grandfathers, uncles. Some were pregnant as a result of this sexual violence. Once again, the girls were separated from the boys, locked in a room, and not permitted to leave even to go to the bathroom, even with dozens of police and guards at the door. They started the fire out of desperation. It was their last attempt at a desperate call for help, a call so that someone would take notice and help them and care for them. They were, after all, in a Safe Home and supposed to be receiving care. From the Guatemalan government. Tragically, that last call for help was never answered.

Finally, everyone is pointing fingers and no one wants to assume responsibility and accountability. Some authorities have been captured: Carlos Rodas, former Head of Secretary of Social Welfare; Sub-Secretary Anahí Keller; and Santos Torres, former director of Hogar Seguro. Up against accusations of State negligence, President Jimmy Morales and a number of members of Congress are trying to wipe their hands clean of any responsibility. The International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG) and the FBI are getting involved in the investigations. At the time of this writing, more and more testimonies and facts are emerging, and only time will tell us who are those accountable.

“Make your indignation convert itself into action! #IAmNotIndifferent”

There are many questions, much anger, and overwhelming grief. I find myself unable to not read articles from various news sources as soon as they are published. But what now? This tragedy happened, and the pain cannot be reversed, but we must ask ourselves: what concrete steps can we take to not be indifferent or ignorant? How can we disseminate information, educate, and make sure that this isn’t repeated in the future?

MIA’s preventive education work champions for gender equality by dismantling and analyzing root causes of violence against women and girls, and violence also against men and boys (from a gender perspective). The Canada-based White Ribbon Campaign (in Guatemala, Hombres Contra Feminicidio, or Men Against Feminicide) is an international campaign to involve men and boys to vow to not perpetrate violence against women and girls, and to educate their peers to do the same. Imagine if the fathers, grandfathers, and uncles of the girls in Hogar Seguro had received the MIA’s Diplomado course? What about the teachers, staff, masons, and guards and police?

Time, energy, resources, and care & compassion must be invested in Guatemalan girls, boys, and adolescents, now more than ever.

Crosses with flowers, candles and fake blood, at the memorial in the Central Plaza

[1] Orellana, Paula. “Misoginia: hogar inseguro e irresponsabilidad estatal.” CMI-Centro de Medios Independientes. 9 marzo 2017. https://cmiguate.org/misoginia-hogar-inseguro-e-irresponsabilidad-estatal/

[2] Woltke, Gabriel y Martín Rodríguez Pellecer. “Las razones del amotinamiento de las niñas del hogar.” Nómada. 9 marzo 2017. https://nomada.gt/las-razones-del-amotinamiento-de-las-ninas-del-hogar-seguro/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Nómada. “Estos testimonios apuntan a un crimen de Estado.” Nómada. 13 marzo 2017. https://nomada.gt/estos-testimonios-apuntan-a-un-crimen-de-estado/

[5] Nómada. “Estos testimonios apuntan a un crimen de Estado.” Nómada. 13 marzo 2017. https://nomada.gt/estos-testimonios-apuntan-a-un-crimen-de-estado/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Muñoz, Geldi y Jessiva Gramajo. “Unicef y PDH denunciaron la situación del Hogar Seguro.” PrensaLibre. 9 Marzo 2017. http://www.prensalibre.com/guatemala/comunitario/unicef-y-pdh-denunciaron-la-situacion-del-hogar-seguro-virgen-de-la-asuncion

[8] Orellana, Paula. “Misoginia: hogar inseguro e irresponsabilidad estatal.” CMI-Centro de Medios Independientes. 9 marzo 2017. https://cmiguate.org/misoginia-hogar-inseguro-e-irresponsabilidad-estatal/

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network