By Samantha Serrano

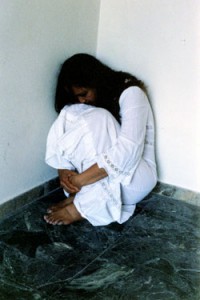

On average, two women are killed every day in Guatemala. At least 4,000 women have been murdered in the Central American country since 1999. (1) More than 500 women have been slain in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico since 1993. (2) This city is often referred to as the City of Lost Girls. Many activists believe the statistics the Mexican government admits are very conservative and the number of women killed is more likely in the range of 4,000 to 6,000. (3)

What is just as staggering as the volume of murders in the two regions is the manner in which many of the women are killed. Women’s corpses in both areas of Latin America are found mutilated, strangled, burned, decapitated, raped, and abused. Bodies have been found with skulls crushed in, fingernails pulled backwards, wrapped in barbed wire, or with the word venganza (Spanish for vengeance) carved into the body with a knife. (4)

The term used to define such high numbers of violent homicides of women is femicide. According to Diana Russell, the author of Femicide in Global Perspective, femicide is not simply the murder of females, but rather “the killing of females by males because they are female.” (5) I believe that the presence of machismo and impunity in both Ciudad Juárez and Guatemala, paired with independent historical and contemporary tensions within each region, have fueled the two epidemics of femicide. This situation has instigated a cry for both women’s rights and human rights.

In many people’s minds, machismo walks hand-in-hand with Latin American culture. Machismo is an overemphasized masculinity centered on the domination of women. (6) This is typical in patriarchal societies where violence against women has become a cultural norm and an accepted custom for centuries. Machismo is present in both Guatemala and Ciudad Juárez and has been established since the time of the Spanish conquest.

When the Spanish settled in Central and South America, they brought every aspect of their culture with them, including how they treated women. Spain, although it is rapidly changing, has historically been a patriarchal society in which men controlled women. In patriarchal societies, women serve as bearers of children and housewives while remaining financially dependent upon men. In patriarchal societies men dominate both politics and households. (7)

The societal belief that women are inferior to men promotes violence against women, just because they are women. Psychologically it becomes a man’s right in a patriarchal society to invade a women’s body through rape, other forms of violation, or murder. Machismo promotes a need to exterminate or dominate uncontrollable women to maintain patriarchal systems. The result of the need for male dominance that causes some men to murder women is femicide.

For many men in Ciudad Juárez and Guatemala, machismo is a cultural norm and for some men being macho is a good thing. Macho is often understood as being a term used to describe an honorable man or a good provider for one’s family.

Sociologist David T. Abalos believes that many Latino men have internalized the deception that Spaniards, other Europeans, and white Americans are inherently better than Mestizos. Abalos says that the Mestizo men of places like Mexico and Guatemala internalize this notion and continue to comply with how society expects them to behave. The inherited idea of male dominance, which culturally appears to be the only place Latino male’s power remains, translates into a manifestation of violence towards women in order to maintain control. If a woman attempts to become more independent and this dominance fractures, feelings of insecurity and inferiority arise and a man is more likely to become violent toward the women in order to regain power. (8)

Machismo also continues to be a norm in contemporary Latin American society due to the fact that the majority of police officers and officials running the justice system are men. Often times in both Ciudad Juárez and Guatemala when women file complaints that their husbands have abused or raped them, the police officers do not get involved and tell the woman that the dispute should be left between her and her husband.

Machismo within the justice system is one of the factors that cause impunity for crimes against women. Considering the lack of laws for women’s protection from violence, the unwillingness or ignorance of a majority of the people involved in the justice system, and the lack of training and supplies for crime investigators and prosecutors, impunity for men who commit femicide seems almost positive.

Of the 1,500 women that were assassinated between 2003 and 2007 in Guatemala, only 14 cases ended in a prison sentence. (9) Only one percent of the cases involving femicide in Ciudad Juárez have resulted in prosecution and sentencing. (10) Low rates of prosecution and sentencing found in both Ciudad Juárez and Guatemala send a clear message to potential assassins that they can and will get away with murder.

In both Guatemala and Ciudad Juárez authorities are quick to blame gang violence and prostitution for unsolved murders involving both men and women. (11) The former President of Guatemala, Oscar Berger, said in June 2004 that in a majority of cases involving femicide, “the women had links with juvenile gangs and … organized crime,” although he did not site any evidence to support that.

In 1995, the Chihuahua State Assistant Attorney General blamed women of Ciudad Juárez who worked all day and then went out dancing and drinking all night for the femicide. He said they invited rape and murder and the large number of assassinations was their fault for going out alone and not holding to the societal expectations of women. Government officials placed ads throughout the city that said, “Do you know where your daughter is?” That same year, fifty-two women were murdered in the city, which was the highest number up until then. (12)

Most police and crime scene investigators in both Guatemala and Ciudad Juárez lack proper training to solve cases. In Ciudad Juárez evidence is often mishandled. Police investigators have misidentified bodies and have given some victims’ families remains of the wrong victims. Some crime scene investigators do not use gloves to handle evidence and do not use bags to place and transport evidence.

In Guatemala femicide victims’ families have reported that victims’ clothes are often returned to them rather than kept as evidence, and DNA testing is not done. Despite the existence of an anti-kidnapping squad in Guatemala, police customarily stall searches until three days after a person is reported missing.

One of the reasons officers are so poorly trained is their low wages. Both the Mexican and Guatemalan government fail to allocate enough money to pay officers adequate salaries. To make up for their low wages, police and government officials in both regions often take bribes as well. Bribes to traffic officers are as customary as highway tolls. Officers and other officials can be bribed to tamper with evidence or ignore a crime. (13)

The laws in both Mexico and Guatemala have done little to protect women from domestic abuse and rape. Both domestic abuse and rape have been linked to female homicides. Until late 2006 in Guatemala, a rapist could legally escape charges if the father permitted him to marry his victim and she was at least 12 years old. (14) Domestic violence cannot be prosecuted unless signs of injury are still apparent 10 days later and marital rape is not a criminal offense. A law empowering men to prohibit their wives from working outside the home was revoked only in 1999. (15)

Women in Mexico cannot file domestic abuse charges if their injuries take less than fifteen days to heal. If a rape victim is twelve years of age or older and a proven prostitute, there can be no charges filed against the perpetrator because authorities consider the victim an active participant. If it is believed that a rape victim led the attacker on and then refused to have sex, the perpetrator will only have to serve one to six years in prison. Forced penetration by anything other than a penis is not considered an act of rape in Mexico. (16)

Although femicide in both Guatemala and Ciudad Juárez can be credited largely to machismo and impunity, both regions have independent factors and histories that have helped catalyze the two separate epidemics. Guatemalans took in a thirty-six year civil war that included the largest per-capita genocide ever experienced in independent Latin American history. The people of Ciudad Juárez have experienced a radical change in the labor force from male domination to female due to the development of maquiladoras.

Mass murders, rape, and torture are not new to Guatemala. An American-organized rightist military coup violently overthrew the government of the elected president, Juan Jacobo Arbenz, when he tried to initiate land reform in 1954. The coup led to more than three decades of civil war between the army and left-wing guerrillas. Before it ended in 1996, more than 200,000 were killed. A large percentage of the victims in Guatemala were indigenous people slain by the army in a government-mandated genocide. A United Nations-sponsored truth commission calculates that the army is responsible for more than 90 percent of the killings during the civil war. (17)

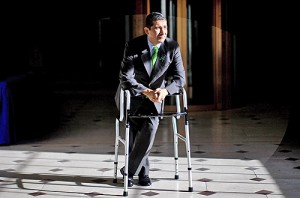

During the civil war, women were seen as spoils of the battles that soldiers could use however they wished. Women made up about a quarter of those killed during the war, although they almost never participated in fighting or politics. Rape was often used as a scare tactic and a display of power by the military. Soldiers or paramilitaries would often cut fetuses from the wombs of victims because they claimed the unborn babies were potential rebels. Violence against women today seems to be a continuum of the violence committed during the war. Many of the people considered responsible for the random murders, rapes, and genocide during the war have taken on positions of power in post-war Guatemala. Some of their jobs include politicians, police officers, and high-ranking officials in the military. Former dictator Efrain Rios Montt ruled during perhaps the most violent time of the civil war and perpetuated the genocide of the indigenous people between 1982 and 1983. Rios Montt became a member of congress both during the war and after the peace accords were signed between 1990 and 2004. After instigating riots in the streets of Guatemala City in 2003, he was able to run for President. Thankfully, he lost by a landslide. (18)

Even though Rios Montt is currently on trial in Spain for human rights violations during the war, his lasting effect on Guatemala’s post- peace accord government exemplifies how the violence of the war is engrained in present-day Guatemala. According to Guatemalan-American artist and radio producer Ana Ruth Castillo, “A lot of violence was taught, indoctrinated, and institutionalized (during the civil war), and I think that our generations now are still victims of that and have not been able to heal from that.” (19)

The violent society that the people became accustomed to living in during the war is still thriving today. In spite of the 1996 peace accords, Guatemala has one of the worst homicide rates in the world. The fact that victims of femicide are often killed in the same ways they were killed during the war is proof of the lasting impression the violence of the war has left. As women attempt to gain more rights and change society in post-war Guatemala, they not only face machismo, but they also battle for rights against politicians and officers who formerly instigated genocide and used rape as a weapon. To several of these men, women’s rights are not an option. Women who seem to challenge traditional gender roles by working, wearing sandals, drinking alcohol, or having a belly button ring are often victims of femicide. (20) Castillo explained, “Because violence is so cyclical between families and partners it has gone past the civil war and it is still very present.” (21)

The women of Ciudad Juárez live in distinctly different conditions from those of the women in Guatemala. Ciudad Juárez is the Mexican city across the border from El Paso, Texas. Since the U.S./ Mexican border was established, there has been great economic disparity between the two cities. Ciudad Juárez has inherited violence due to the ongoing battle to bring illegal drugs into the United States across the border. The drug wars in 2008 put death tolls at record highs. One aspect of border towns that many people overlook, however, is the maquiladora.

Maquiladoras are factories set up by foreign companies (mostly American) in Mexican border towns. Maquiladoras were rare until the Mexican government launched the Border Industrialization Program (BIP) in 1965 to bring business and employment back to the border cities after World War II. (22) The BIP granted licenses to foreign companies (mostly from the United States) for the tariff-free importation of machinery, parts, and raw materials. The surge of foreign factories marshaled in the maquiladoras. The businesses that came to Mexico, however, did not desire male workers. They desired female workers because they were more docile, submissive, and cheaper than male workers. When the Mexican government passed the BIP they unintentionally converted Mexican border towns into manufacturing sectors. Migrant workers from rural areas rushed to the border towns seeking employment at the maquiladoras. The flow of discouraged migrants seeking employment, as well as transient workers hoping to hop the border to the U.S., resulted in over-crowding of the city and a high crime rate.

Skyrocketing female employment and plummeting male employment changed the makeup of the workforce in Ciudad Juárez. Female maquiladora workers became the main wage earners in the home. Although women seemed to achieve greater financial independence, husbands, fathers, and brothers did not normally allow women to play a significant role in household decisions. In actuality, the switch to women becoming the main breadwinners in the home caused most men to tighten their control over women. The typical male usually refused to resign from his position as head of the household and would not help with housework or cooking. Female maquiladora workers had to take on the responsibilities of cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the children in addition to a ten-hour workday. (23)

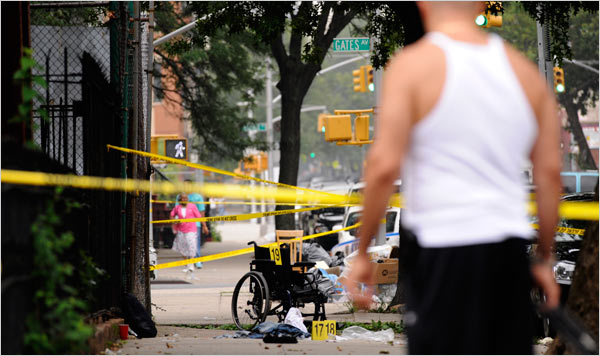

In 1993, the corpses of young females started appearing in the deserts on the outskirts of Ciudad Juárez. Before 1993 most murders in Ciudad Juárez were drug and gang-related. However, the majority of the victims found at this point had no relation to either gangs or drugs. (24)

As the bodies began emerging, tensions concerning male domination and employment were gaining momentum due to the upcoming passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which would further empower the maquiladoras and augment female employment.

The passage of NAFTA in 1994, which allows for an economic open trade policy between the United States, Mexico, and Canada, caused a renewed surge of maquiladoras in Juárez, as predicted. More than 400 maquiladoras now operate in Ciudad Juárez and continue to produce billions of dollars in exports. Young women from other parts of Mexico migrate to the already overpopulated Ciudad Juárez hoping to find economic security in Juárez’s maquiladora job market. (25)

Thousands of young women in Ciudad Juárez commute to maquiladora jobs every day before sunrise to work ten to twelve hour shifts where they will be lucky to make $5 a day. The women often have to walk in dangerous areas with little outdoor lighting in the shantytowns outside of Ciudad Juárez to arrive at the nearest bus stop to get to work. A 20-year-old woman named Claudia Ivette once arrived three minutes late for her shift at a maquiladora and was turned away into the dark night. Her body was later found in a ditch alongside the corpses of eight other women. (26)

With increased employment tensions and women forced into unsafe situations to keep employment at the maquiladoras, femicide in Ciudad Juárez has escalated. Last year saw the highest number of victims of femicide, with eighty-six women’s bodies found. (27) More than fifty percent of femicide victims are maquiladora workers.

Maquiladoras also illustrate the cultural idea of female disposability. (28) This disposability refers to the excessive turnover rate of employees in the maquiladoras. Another reason maquiladora managers prefer to hire women is because they are less likely to strike. Women in maquiladoras can be fired for any reason. If a woman does not meet the company’s weekly goals of production or if a woman gets pregnant it is automatic grounds for termination. Women’s activist Esther Chávez claims that the attitudes of maquiladora managers toward female workers with regards to their disposability have permeated the minds of the men of Ciudad Juárez. They take on the belief that the bodies and lives of women are also disposable. (29)

Maquiladoras promote segregation and competition between men and women in the work place as well. Maquiladora managers separate the sexes in the workplace. When male workers do not meet the maquiladora’s standards or are disobedient, they are forced to sit with the female workers as a penalty.

The tactics used by the maquiladora manager give the male workers a feeling of superiority. When they are “punished” by having to sit with the women, they feel their masculinity is threatened. This could result is a violent reaction towards the women they are forced to be in the company of.

Perpetrators of femicide also have an advantage in that many of the maquiladora workers are transients from other parts of Mexico. (30) It is not likely that victims with few or no ties in the area will be searched for. Several women’s remains are found in the deserts on the outskirts of Ciudad Juárez that are never claimed or identified. If there is no one battling for a murder case to be solved in Ciudad Juárez, officials do not bother with an investigation. (31)

The exact causes or motives in each case of femicide in Guatemala and Ciudad Juárez will never be known. One would have to question the murderers of the more than 3,000 woman in Guatemala and 500 women in Ciudad Juarez. However, one can be sure that the presence of impunity for the perpetrators of femicide as well as the cultural acceptance of male domination over females, or Machismo, has played a role in or contributed to the killers’ willingness and desire to take the lives of innocent women. The scars of civil war and genocide in Guatemala, as well as indoctrinated violence, have contributed immensely to the contemporary epidemic of femicide. The defensive reaction to the change in employment in Ciudad Juárez due to the maquiladoras, as well as the anonymity and disposability of such a large portion of the female population, has contributed to the motives behind femicide in the border town.

As more and more bodies turn up in both regions, more and more men and women join the fight against femicide. There is an ongoing battle by Nongovernmental organizations, concerned citizens, and victims’ families and friends against the acceptance of femicide and the murderers. (32) They claim that although more men are murdered than women in both Ciudad Juárez and Guatemala, people must take into account the way these women are killed. While men are normally just shot or stabbed, women are raped and then seriously mutilated. The manners in which the women are murdered exhibit hatred towards the female sex that is also apparent in how women are treated while they are alive. The fight against femicide is a fight for the rights of all women, dead or alive.

As Guatemalan sociologist Ana Silvia Monzón said, “We have to recuperate the feeling of living, of living well…. We are not able to continue in this dynamic of poverty, of discrimination, of racism, and of machismo that only brings us destruction.” (33)

— Sam Serrano is currently earning her M.A. in Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Sam graduated from California State University of Fullerton in May 2009 with a double major in Spanish and Latin American Studies and a minor in Journalism. She plans to continue her work for human rights in Guatemala throughout the rest of her career.

……………………………………………………………………..

(1, 33) Ana Silvia Monzón, personal communication, December 14, 2008

(2, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 22, 23, 24, 26, 28, 29) Panther, 2007

(3) Gwin, 2008

(4, 7, 20, 32) Lucia Muñoz, personal communication, December 19, 2008

(5) Russsell, 2001

(9, 11) Lakshmanan, 2006

(14) Benitez, 2007

(15) Impunity Rules 40-42

(17) Tuckman, 2007

(18) Aznarez, 2008

(19, 21) Ana Ruth Castillo, personal communication, December 14, 2008

(25, 30, 31) Osborn, 2004

(27) Washington Valdez, 2009

Bibliography

Gwin, Sara (2008, February 19). Alarming rates of femicide in Latin America. Oregon State U, Retrieved April 18, 2009, from http://global.factiva.com.lib-proxy.fullerton.edu/ga/default.aspx

Russell, Diana (2001). The Politics of Femicide. New York: Teachers College Columbia University Press.

Panther, Natalie (2007). Violence against women and femicide in Mexico: The case of Ciudad Juarez. The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection, Retrieved April 18, 2009, from http://www.proquest.com.lib-proxy.fullerton.edu

Lakshmanan, Indira A. (2006, March, 30). Unsolved Killings Terrorize Women in Guatemala. Boston Globe, Retrieved April 19, 2009, from http://proquest.umi.com.libproxy.fullerton.edu/pqdweb?did=1012172451&Fmt=3&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&

Benitez, Ines (2007, November, 26). Right- Guatemala: Impunity Fuels Violence Against Women. NoticiasFinancieras, Retrieved April 19, 2009, from http://proquest .umi .com .lib -proxy .fullerton .edu/pqdweb ?did=1388399061 &Fmt=3 &clientId=17846 &RQT=309 &VName=PQD

Tuckman, Jo (2007, May, 10). An untold massacre. ail & Guardian Online , Retrieved April 21, 2009, from http://global.factiva.com.lib-proxy.fullerton.edu/ga/default.aspx

(2006, November 18). Impunity Rules. Economist, 40-42.

Aznarez, Juan Jesus (2008, February, 13). The killing fields of Guatemala. El Pais , Retrieved April 21, 2009, from http://global.factiva.com.lib-proxy.fullerton.edu/ga/default.aspx

Washington Valdez, Diana (2009, January, 26). U.N. official to visit slain women’s families in Juárez. El Paso Times, Retrieved April 16, 2009, from http://www.elpasotimes.com/ci_11559343

Osborn, Corie (2004, March, 1). Femicidio, hecho en Mexico. Off Our Backs, 24, Retrieved April 22, 2009, from http://global.factiva.com.lib-proxy.fullerton.edu/ga/default.aspx

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network

Proud Founder Member of the Guatemala Peace and Development Network